Last year I had the chance to collaborate with graduate student Annuska Zolyomi and Professor Jamie Synder, two incredible researchers at the University of Washington’s Information School to analyze the psychosocial and adaptive aspects of digitally enhanced vision. We were awarded Best Student Paper at the 19th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility.

Globally, 246 million people have “low vision,” an umbrella term used to describe moderate to severe visual impairments. While much of this population is completely blind, a larger portion has partial vision. These individuals can experience acuity loss, high sensitivity to light, blind spots, and other disruptions of the visual field.

With the growing need to provide assistive technologies for people with low vision, we have seen an exponential growth in head-mounted displays (HMDs) that take advantage of recent developments in computer vision, wearable technologies and battery life.

Our research contributes empirical evidence in the form of rich, qualitative descriptions of users’ psychosocial experiences when integrating technology-mediated sight into their daily lives.

For our study, we focused on early adopters of eSight 2.0 eyewear. Marketed since 2013 by Ottawa-based eSight Corporation, the device is currently used by over one thousand individuals with low vision in the US and Canada and has received attention in popular media.

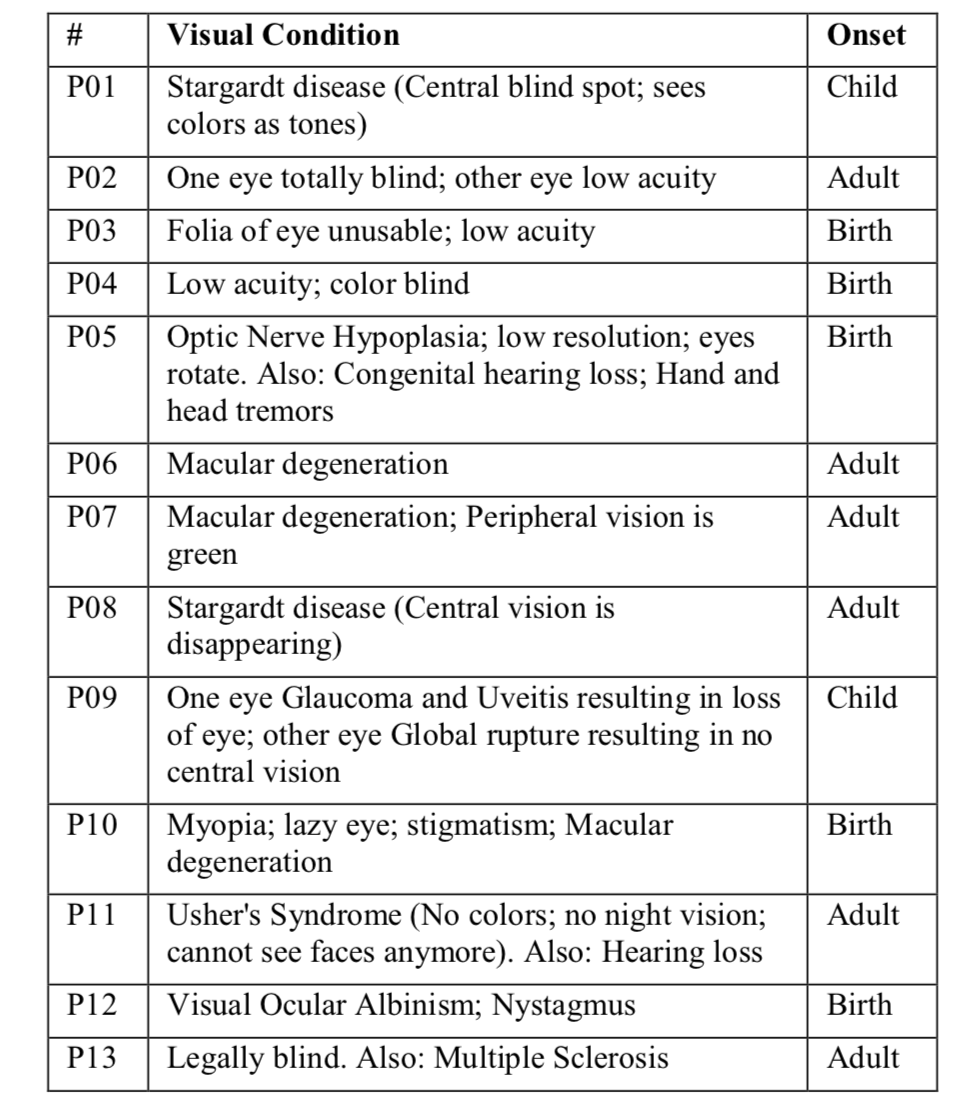

For our user interviews, we worked with eSight to identify 13 users (6 female, 7 male) over the age of 25 (average age of 52) who had a minimum of 5–10 years with vision loss and experienced profound shifts in vision when using the eSight device, as measured by Best Corrected Visual Acuity (BCVA).

We conducted interviews over Skype and telephone, which allowed us to reach a broad geographic range across the U.S. and Canada. The participants were trained or employed in, or retired from, occupations such as information technology support, nursing, marine engineering, teaching, electrician, office administration, kitchen design, and visual art.

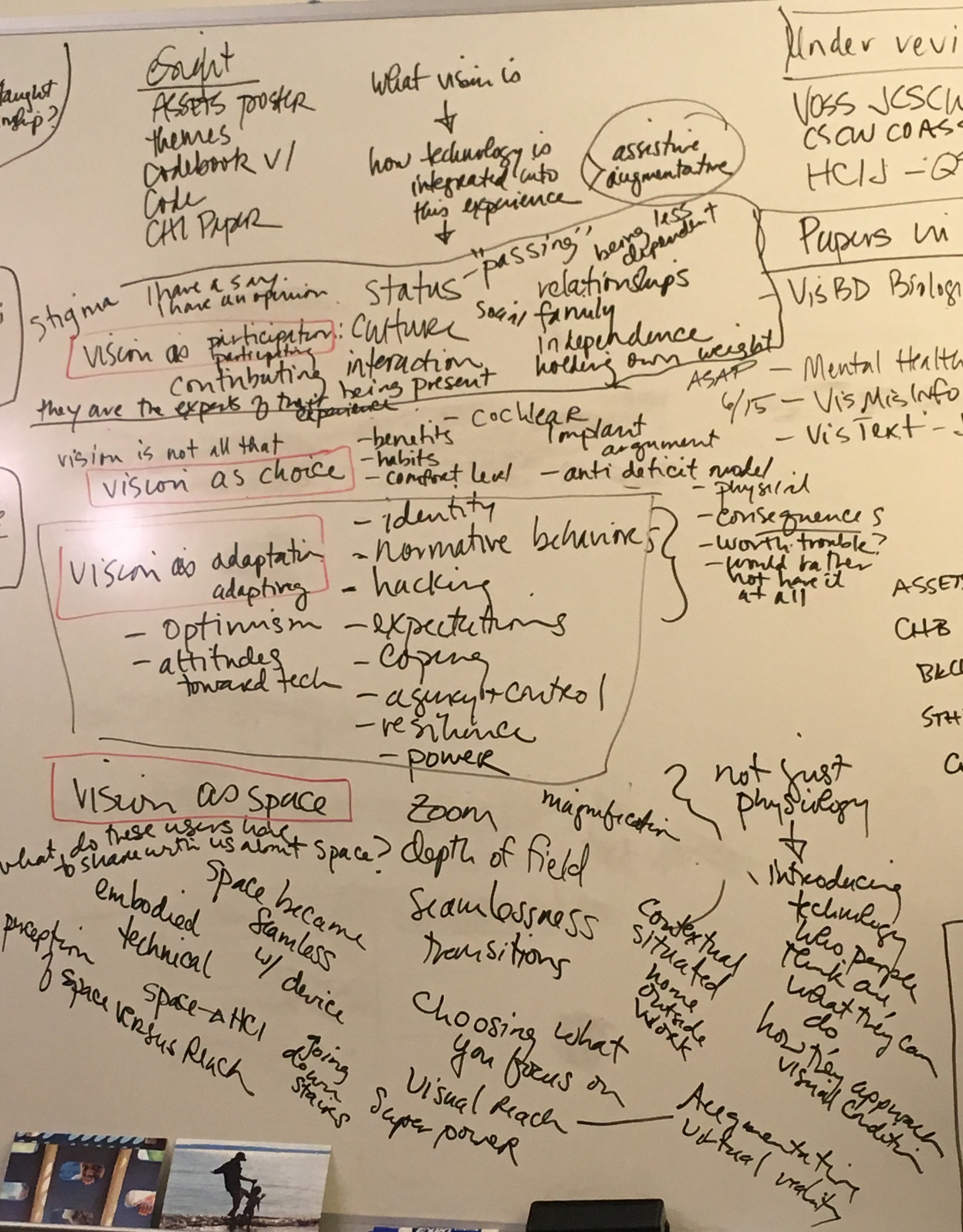

Unlike quantitative analysis that is driven by the probability or measure of occurrence, our research focused on analyzing the qualitative aspects of users that adopt assistive technologies. So in order to create and build a robust analysis model, we began by brainstorming different keywords used by our eSight users to define our emergent themes.

Based off of these themes, we created a Code Book that contained a description as well as example of Codes that we used as reference when highlighting our themes on Nvivo. This step was particularly helpful as we were able to define and discuss what each theme corresponded to and when in doubt acted as our go-to guide. Think of it as our team’s internal dictionary.

After coding all of our transcripts we were able to take a step back and redefine our themes using our overall analysis. These themes were based on grouping and categorizing our 14 codes to produce the following main themes:

One of the main recurring themes we found was based on Assessing the value of Assistive Technologies like eSight. Our participants vividly described their first experiences using eSight, many tearing up as they talked about the “night and day difference” (P03) in their vision, and feeling “blown away” (P06) and overwhelmed:

This helped our stakeholders from eSight understand that though users were reluctant to buy the device initially, due to it’s high pricing ($9,995), they were overall satisfied and overjoyed when using it.

Our next theme was based on Negotiating Social Engagement or rather the instances where our users found themselves having or lacking the ability to participate in day-to-day social engagements. Some described situations where their glasses helped them perform a task while others provided instances where they felt they profoundly contributed to society.

Our next theme, Boundaries of Sight related to the times our users adapted their device to work in different contexts. One of our participant’s described what it meant to “people watch” while using eSight:

Lastly, Attitudes and Expectations of Sight helped us understand how our users have adopted their device and their overall willingness to buy these devices. A lot of our users showed an openness towards this technology while others provided areas of improvement for future iterations.

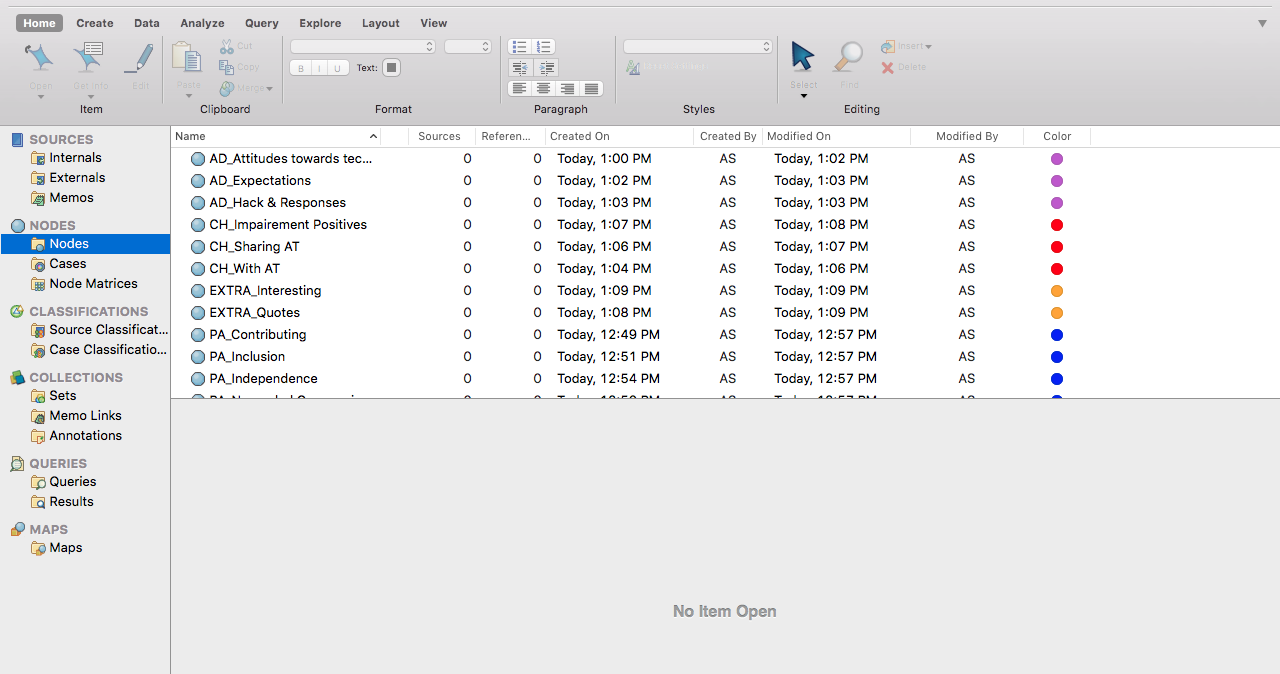

After converting our audio interviews into text, our three person team split up and independently began marking paragraphs that corresponded to a respective theme. Using the 14 codes we defined in our code book, we were able to standardize our qualitative analysis in order later conceive our main themes.

One of the drawbacks of using NVIVO at the time of our coding (Summer 2016) was the lack of team collaboration in its software. We tried to look for alternative softwares but ended up using Google Drive and creating a system that made file sharing and merging easier for our team. NVIVO 11 now supports Team Collaboration!

Since our team was relatively small, our hack was to come together every few days to discuss our progress over long Skype sessions. We walked through each transcript and justified our coded sections and came to a consensus for each section.

Looking back at my college career, I am fortunate to have had this opportunity to work on such impactful and cutting edge work. Often times undergraduate students are made to do boring-old grunt work, and sometimes rightfully so, but I am grateful to both Jamie and Annuska for treating me as an equal and giving me all the resources necessary to contribute and collaborate. What started off as a 2 credit independent research project (Spring 2016) ended up translating to a 7 month long engagement most of which was virtual since I was interning in India the Summer of 2016. Not going to lie, most days that summer were 17 hour ones.

This project gave me the perfect blend of working independently whilst in a team. Each of us brought something different to the table and it was our diverse experiences that enhanced a deeper imagination when coding through our interviews.

Furthermore, this study made me realize the importance of channeling our empathy. And of course, had it not been for our users and their rich anecdotes, our findings wouldn't nearly be as thought-provoking.

Overall I am optimistic to the future of assistive and augmented technology and hope to contribute more in the future!